C++ quick tips: Full template specialisation and one definition rule

Recently I’ve been doing a lot of template meta-programming in C++. As we all know, when writing a class or a function template, the definition must be in the header file. This is because the compiler needs to see the definition of the template in order to instantiate it. There are some exceptions to this rule. The restriction doesn’t apply if you explicitly instantiate the template in the source file (and of course limit the template’s use to the set of types you’ve instantiated it with). But there’s one more exception, which I think, is not very widely known - full template specialisation.

*.cpp file or defined inline explicitly!To illustrate the this in practice, I’m gonna start with a simple header file foo.hpp:

|

|

What I have is struct Foo template and its full specialisation for double.

This can be used in a source file like so (this is my main.cpp):

|

|

Now, I’m gonna introduce one more translation unit which uses the template as

well. First, the header file wrapper.hpp:

|

|

and wrapper.cpp file:

|

|

I’m gonna use this code in main.cpp so, its final contents will be:

|

|

I can now, try to build the whole thing:

g++ -I. -c main.cpp

g++ -I. -c wrapper.cpp

g++ main.o wrapper.o -o main

… and no complaints from the compiler. So, what am I talking about?

inline.Because of inline, the one definition rule is not broken. Quoting cppreference:

There may be more than one definition of an inline function or variable(since C++17) in the program as long as each definition appears in a different translation unit and (for non-static inline functions and variables(since C++17)) all definitions are identical…

Let’s make a small change to foo.hpp:

|

|

Now, I have a fully specialised template which is no longer inline. If I try

to build the project again, I get:

|

|

The linker is complaining about multiple definitions of Foo<double>::foo(double).

This is because the definition of the fully specialised template is not

inline neither it is placed in the *.cpp file. One definition rule is

violated.

My preference is to move the code to *.cpp file - this will improve build

times and might have positive impact on code size as well. Here’s my final version of foo.hpp:

|

|

and additionally, I’ve introduced a dedicated implementation file foo.cpp for Foo

containing the full template specialisation:

|

|

One last rebuild attempt will produce the desired results:

|

|

Conclusion

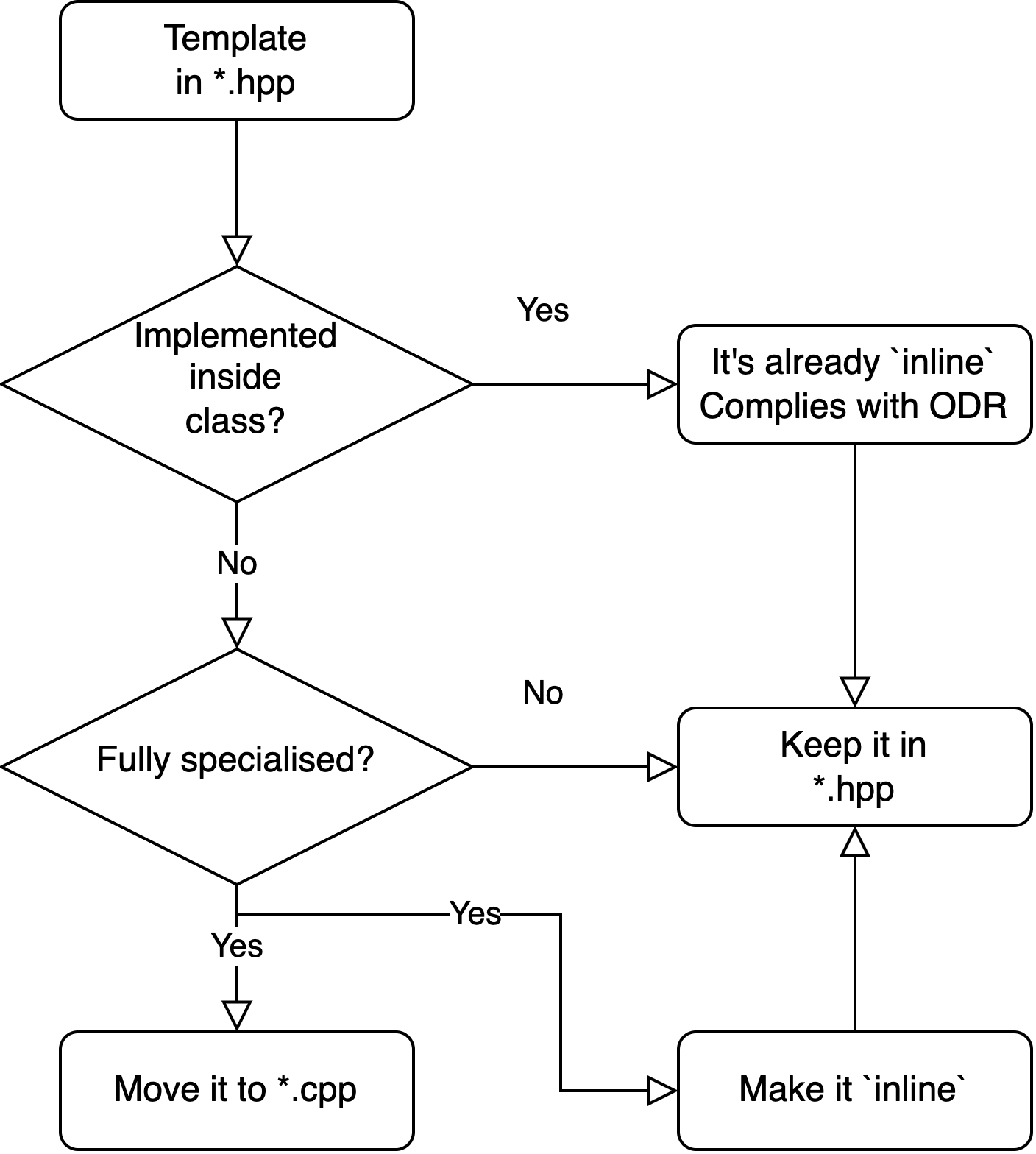

The decision making, when implementing a template can be summarised with the below flow chart.